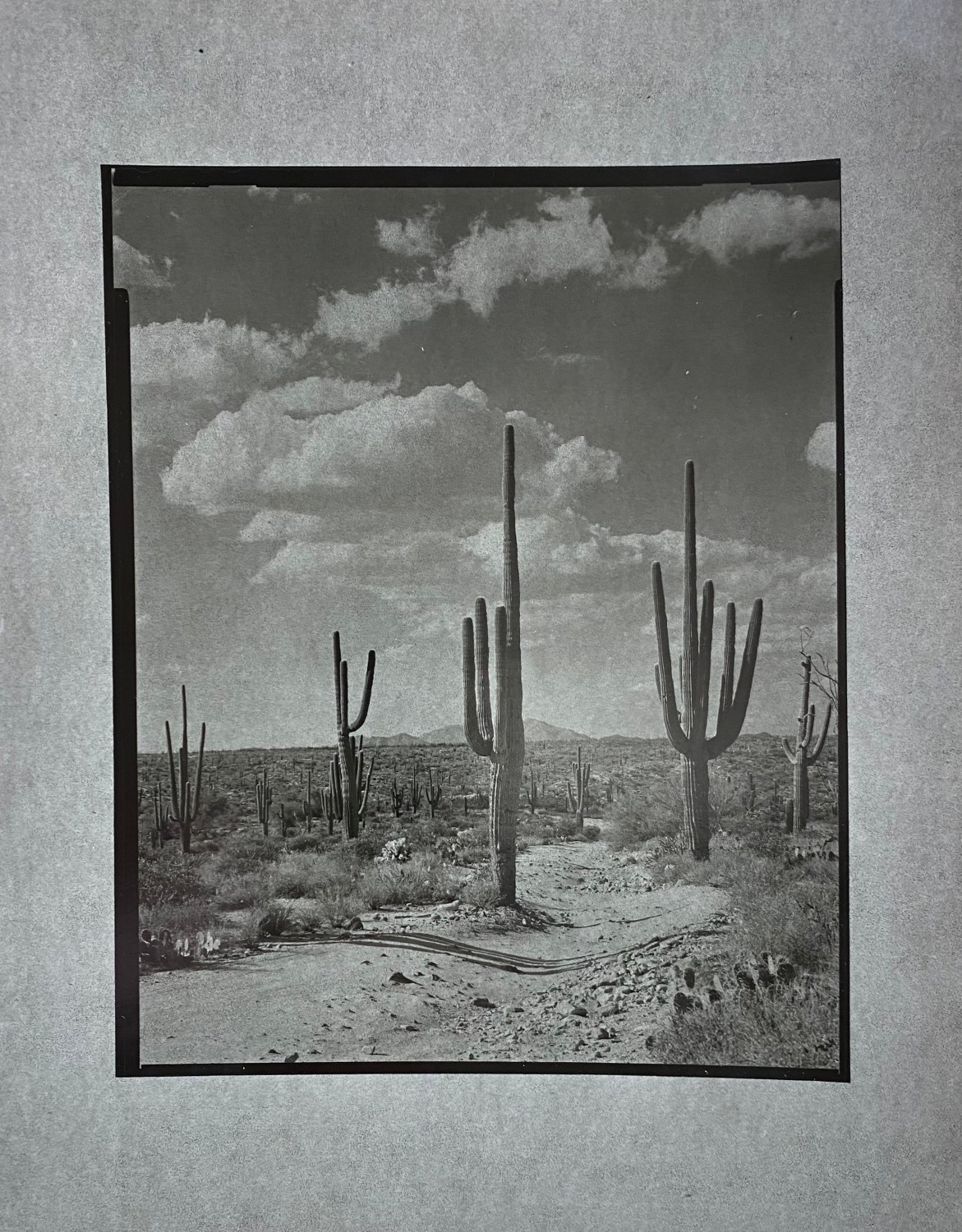

About five years ago, or perhaps a bit more or less—I’m losing track of time these days—I used to drive out to the Four Peaks Wilderness area, navigating four-wheel-drive roads while exploring the landscape and seeking out Saguaros to photograph. In regards to this particular landscape photo, I occasionally incorporate roads into my compositions. While I don’t categorize myself strictly as a landscape photographer, I do consider myself a photographer with diverse interests, and landscape photography is among them. My rationale for including roads is to capture the human presence in the landscape. I’m unsure if there’s a specific term for it, but I refer to these as editorial landscapes. A couple of years after taking this picture, a devastating brush fire swept through the area. I haven’t returned since the fire, but I hope the giant Saguaros survived. This photograph is a silver gelatin darkroom print from an 8×10 inch negative. The grayish print was made with old paper that was severely fogged from heat and age. I included itin this post because I thought it was somewhat of a happy accident.

I came across a comment on someone else’s post where a person wrote there are many photographers promoting their photography on Facebook. I took it as a somewhat negative comment. This made me reflect on it, and I want to push back on that statement. I don’t consider what I do as promoting my work; I’m not directing anyone to a website to buy my art. I don’t actively promote myself, and I don’t even have a website anymore. Most of my followers are friends or colleagues I’ve worked with, and I see it as sharing life stories and experiences that others might enjoy. While some sell their work, my focus is on sharing rather than selling. My photography isn’t typically “pretty”; it’s my interpretation of the world. I don’t shoot to sell; it’s more about expressing how I see things. When I was a photojournalist, I often heard that inner voice saying, “they’ll never use it,” and the same self-doubt sometimes lingers in my head now as no one gives a shit so why bother but I keep going and doing. Enough about that. So here we go again a bit about this photo and its process.

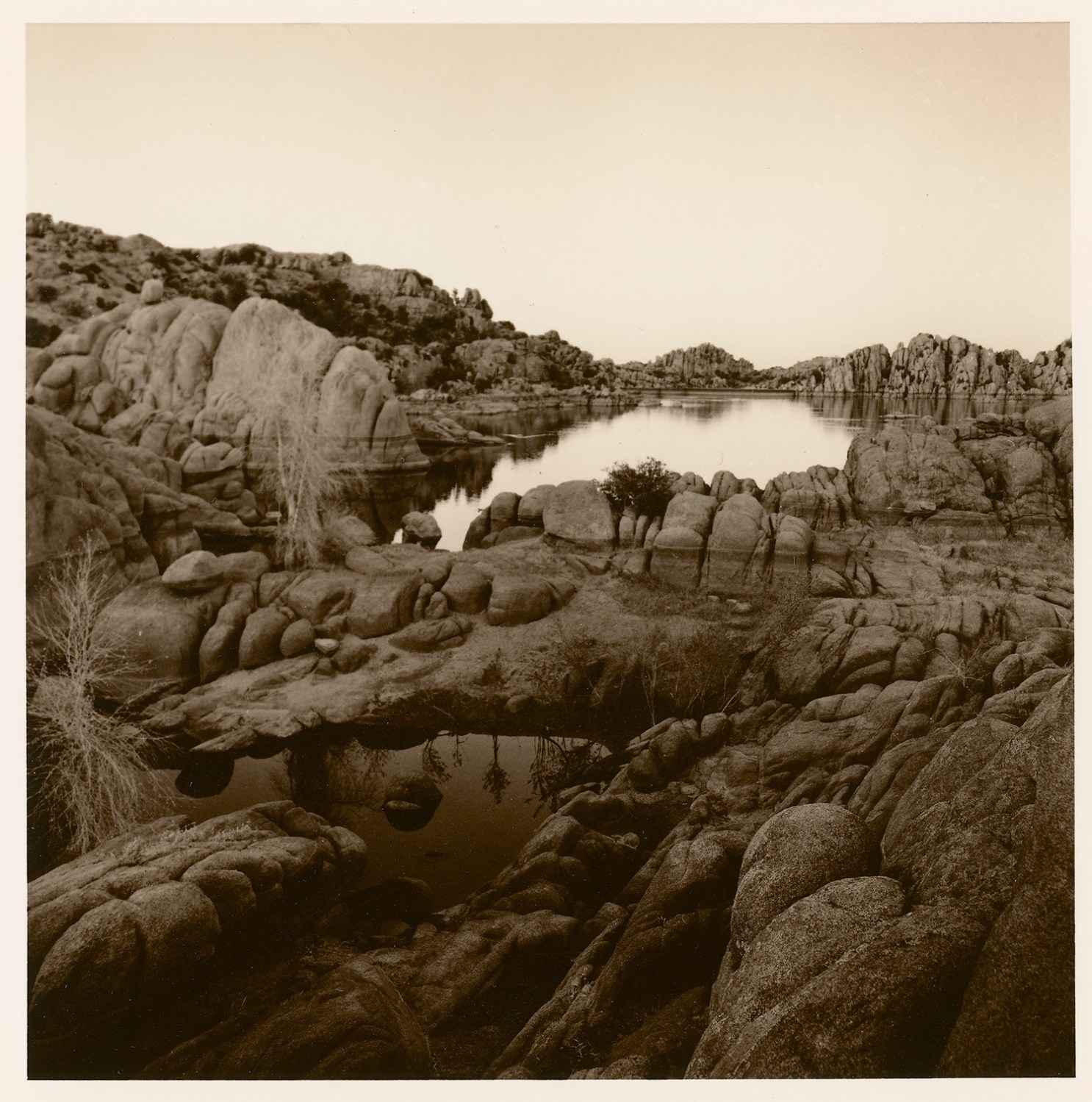

Watson Lake, on black and white film. I made a small print in the dark room and toned it with a toner called Thiourea. It’s a bleaching sepia toner that is beautiful. It gives the print a golden chocolate brown tone that transforms the print into something else. For me it’s a calm, soothing, peaceful warm experience when looking at the print.

I made this picture somewhere in Nebraska. When my father was alive he took my sisters and I on a Nebraska tour. My mother and father where born and raised in Lincoln until my father was recruited into the Army Air Corp. Much later in his life he cared for his mother in the same house he was raised in. He commuted from New York to Lincoln often caring for her. Dad with my mother eventually would spend every summer there. Dad was an avid golfer who played ever golf course within a 50 mile radius of Lincoln. When my sisters and I visited he proclaimed to give us a tour of Eastern Nebraska. Secretly and unbeknownst to us it was a tour of every Eastern Nebraska golf course he played. I made this picture at a gas station while my father was filling up the van with gas. I jumped out and was enamored by the setting sun and the openness of the landscape. I began to wandering around the station with my camera when I saw this stand alone mailbox. Illuminated by the warm setting Sun I was sucked in.

Twelve year ago or so I came into possession of a medium format Polaroid 600SE camera. It’s a large cumbersome camera with a large format Mamiya 127mm lens. The lens has a leaf shutter with f-stops ranging from F-5.6 to F-64 and synches at all speeds up to 500th of a second. Sync’s means I could use a flash or commercial lighting equipment with shutter speeds up to 500th of a second. Most DSLR or SLR film camera’s sync from 30th to rarely 250th at most. Leaf shutter camera’s sync at all speeds.

Primarily the medium format Polaroid 600SE instant film camera was used for checking lighting in studio applications. At the time, I wasn’t doing studio work rather on location marketing work. With the digital camera I can check the digital back screen or while tethered checking on a lap top. For that reason there was no need to use the Polaroid check system anymore.

Shortly after getting the camera Polaroid stopped making the peal apart instant film. I then switched to Fuji instant films. Everything was great! I was shooting all kinds of things including landscape. The Polaroid 600SE has a Mamiya large format lens so the quality was very good. Then some time later Fuji quit making instant film and the camera went on the self as a by gone relic.

Some years later, I decided to do little research and found out I could put film backs on the camera with an adapter. I bought a 6X9 film back for $50.00 and tested it. To my surprise the film was outstanding and very sharp. I bought more backs a second 6X9 and two 6×7 backs.

For me, this new discovery and rebirth of the camera has been exciting and a lot of photographic fun. It’s not a carry around camera and somewhat difficult to load film but I can tripod it or hand hold it with the hand grip trigger built into the camera. Below are dark room prints, two silver gelatin 6X7 and two silver gelatin 6X9 prints I made with the Polaroid 600SE camera and printed in my darkroom.

After all these years of shooting and evolving with digital photography, I have mostly returned to film. You might ask why? Some reasons are, I’m retired now and I don’t want to continue upgrading digital cameras every few years. I don’t have to upgrade or update my analog cameras. I can buy a lot of film for the price of a new system and besides film is still beautiful. Shooting B&W film has always been my escape and very personal for me where I can be creative all by hand. Although, analog is a slow, daunting process, the results for me are worth the time spent in the darkroom. It tests every aspect of my skill and craft as a photographer. When it comes to my darkroom prints, I’m somewhat of a perfectionist and they need to be worthy of a wall. What hinders me in making prints is it can take hours to produce but when I mat the final print, it truly becomes an art piece. With my silver gelatin prints, I’ve had them in shows with “not for sale” on them. I’m so attached to the images and the work that goes into making them, I can’t separate myself from them. I’ve convinced myself people can’t pay me enough to give them up. As I’m getting older, maybe I could choose to get over my stubbornness and consider some options. I’ve been thinking about a project where people could collect my work but that’s way down the line.

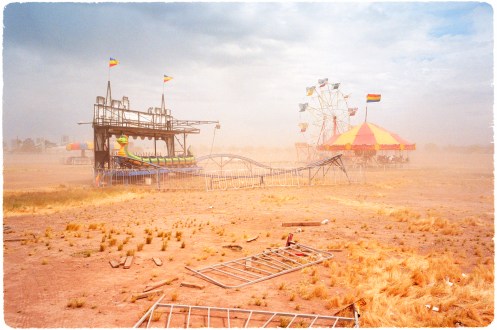

Driving west on Interstate 8, a fellow photographer and I were on the hunt for an intriguing photograph. It felt like we had been driving for hours under the hot, cloudless sun of the Sonora Desert in Arizona. We had left the small town of Gila Bend behind us and were heading west, inching closer to Yuma, Arizona. It was almost two hours into the journey, and we still hadn’t found anything to capture our interest.

Desperate for a subject, we kept scanning for anything that would compel us to stop and photograph. Just as I was about to lose hope, something caught my eye. A large white structure that looked like an old gas station canopy. By the time I noticed it, I had already passed the exit. I had to drive a few more miles before finding a spot to turn around.

When we finally made it back, there it was: a large, freestanding canopy. It stood alone, seemingly out of place, and practically begging to be photographed.

It appeared to be the remains of an old gas station, yet there was no evidence that a station had ever been there. No concrete slab, no pumps, nothing. I began to wonder about its purpose. Perhaps, it was a shady rest stop for weary travelers escaping the blazing sun or maybe a quiet spot for police officers catching up on paperwork. Either way, we didn’t spend too much time pondering. It was time to start shooting.

I got the 8×10 Arca-Swiss large-format camera out and began composing a shot. As I gazed through the ground glass, the oddity of the scene filled me with curiosity. This was the kind of unexpected find I love to photograph.

As with many of my photographs, I planned to revisit the site later, hoping for better light or a dramatic sky that might transform the image. But when I returned, it was gone.

Just like that, the canopy had disappeared, leaving only the memory of that strange and solitary moment in the desert.

A couple of months ago, my wife and I celebrated our 45th wedding anniversary with a memorable getaway to Williams, Arizona. We stayed at the Grand Canyon Railway Hotel. Williams, is a small town along the old Route 66 that is full of history and character. One of the highlights of our trip was attending a Western-themed shootout show before boarding the iconic train.

During the performance, I captured a candid moment that spoke volumes to me: a young boy’s curiosity and fascination as he watched one of the actors makes his entrance into the set. His wide-eyed wonder reminded me of the magic of childhood—when the world feels full of mystery and adventure. It made me reflect on what it might be like to see life through a child’s eyes again.

I’m not entirely sure if this image qualifies as traditional street photography, but it undeniably captures a candid and authentic moment of human connection. For me, that’s the essence of storytelling through a lens.

I often listen to podcasts by younger photographers who dismiss older ones as stuck in the past. They joke about how we cling to the “good old days” of shooting film and suffering for our craft. Implying we’re irrelevant in the digital era.

Sure, it can get tiresome to hear old stories over and over. But dismissing or canceling older photographers overlooks their value. These stories come from a place of loneliness. Many older photographers have lost peers or simply lack someone who understands their journey. Sharing their experiences is an attempt to stay relevant and connected.

As an older photographer myself, I’ve learned not to dwell on the past or preach about film days. I’m still shooting, still learning, and still evolving as a lifelong student of photography. But I’ll admit, I miss the days when my name carried weight in the local photographic community. Losing relevance stings, even if you accept it gracefully.

There’s truth to the saying, “Keep up or get left behind.” I’ve embraced both analog and digital photography, enjoying the resurgence of film and the beauty it offers. My personal work balances both—street photography and portraits are digital, while my art leans analog.

Photography evolves, and so do we. For me, it’s not about clinging to the past but continuing to create, experiment, and grow. Stay curious, or risk getting left behind.